Stay in the loop! Subscribe to our mailing list

This article is written by Enora Bennetot Pruvot - Deputy Director for Governance, Funding and Public Policy Development, EUA.

Autonomy remains a necessity for institutions’ ability to fulfil their core missions. University Autonomy in Europe IV: The Scorecard 2023, published in March this year by the European University Association (EUA), collects, compares, and weights data on university autonomy in 35 higher education systems. The report identifies several notable trends across Europe. These include aspects related to changing governance models, consolidation of the higher education landscape, transnational university collaboration, underfunding challenges, tensions around campus real estate, evolving academic careers and issues related to internationalisation, to name a few.

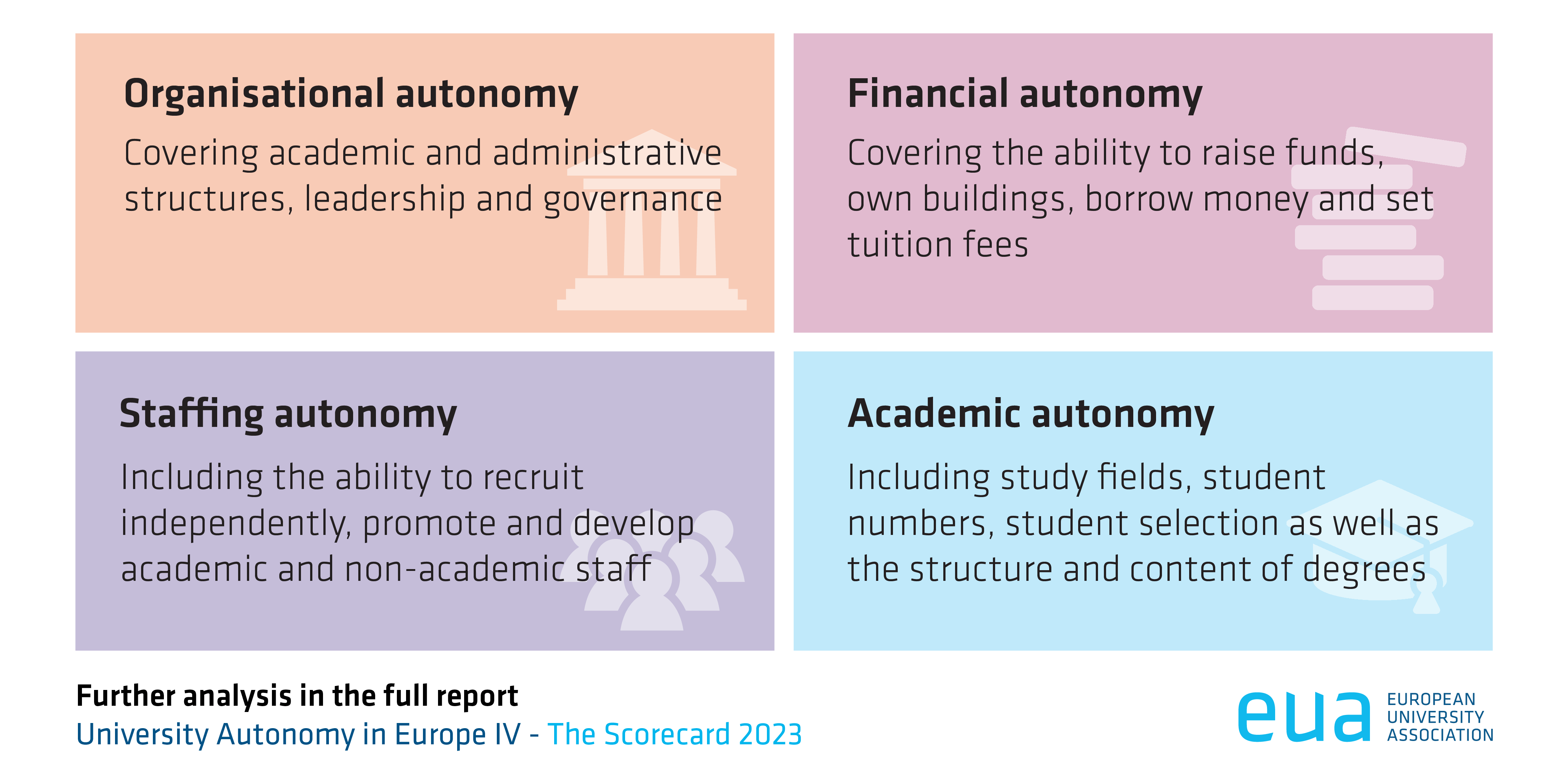

University autonomy contributes significantly to successful transnational cooperation, no matter the collaboration format or scope, the number and diversity of partners – the European university alliances being one of the most recent additions to a wealth of cooperation models. Diving into the four dimensions covered by the Autonomy Scorecard, one may identify some related limitations at organisational, financial, staffing and academic levels.

Organisational autonomy matters for international cooperation. The capacity of universities to establish or engage with other legal entities is one example.

Financial autonomy can support transnational cooperation. Flexibility in the internal allocation of financial resources is important to implement measures agreed on by the partnership, as project-based funding tends to not suffice.

In the context of academic autonomy, the question of programme accreditation and the possibility to decide on the language of instruction, as well as the selection of students in the context of joint programmes, are essential for transnational cooperation. But in all three areas, universities in many systems still face several restrictions. A notable issue for European university alliances is the need, in some cases, to go through accreditation when the composition of the consortium changes, adding to an already significant administrative burden. ‘Fast-track’ options for alliances were explored in this regard, for instance in Hungary, creating a de facto and de jure distinction between European university alliances and other forms of transnational cooperation. The question remains, whether the dynamics created by the European Universities Initiative may lead to significant system-wide changes, as foreseen in the European Strategy for Universities and the Council recommendation on building bridges for effective European higher education adopted last April, or whether they will remain the exception.

Overall, the Autonomy Scorecard paints a complex picture of the direct and indirect pressures experienced by universities over the past five years. The analysis has shown that the extent of autonomy is not only determined by the legal framework, but also by a variety of accountability arrangements, steering tools, funding models, and, increasingly informal interventions by public authorities.